Pittsburgh’s Youth – Driven Food Boom

By Jeff Gordinier

The New York Times – March 15, 2016

NEW YORK, NEW YORK

PITTSBURGH — It hits you as soon as you get to town.

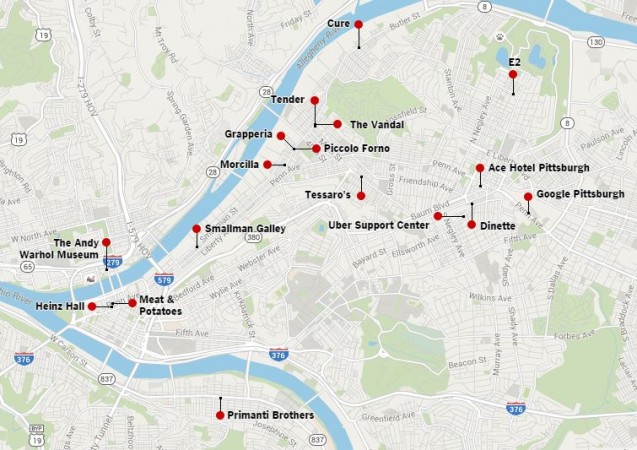

There’s the purple-haired free spirit at the Ace Hotel who gives you the lowdown on outlaw poetry gatherings and killer pizza. There are the art kids offering tips at the Andy Warhol Museum, and the tyro entrepreneurs strategizing over cocktails at the Tender Bar & Kitchen in Lawrenceville, the neighborhood along the Allegheny River that is shifting from a desolate zone where your laptop might get stolen to the place where butcher paper in the windows signifies a bumper crop of new restaurants. There’s the 25-year-old Uber driver who shoots you a crucial heads-up: “The best bartender in the world is working tonight.”

Everybody seems so young. And everybody’s talking about restaurants. If there are scholars who hope to study how a vibrant food culture can help radically transform an American city, the time to do that is right now, in real time, in the place that gave us Heinz ketchup.

In December, Zagat named Pittsburgh the No. 1 food city in America. Vogue just went live with a piece that proclaimed, “Pittsburgh is not just a happening place to visit — increasingly, people, especially New Yorkers, are toying with the idea of moving here.”

Kelly Sawdon, an executive with the Ace chain, said the company spent years trying to raise money to convert a torn-and-frayed Y.M.C.A. into a hip hotel because the “energy” of the city suggested a blossoming marketplace. Food, she said, has been the catalyst.

For decades, Pittsburgh was hardly seen as a beacon of innovative cuisine or a magnet for the young. It was the once-glorious metropolis that young people fled from after the shuttering of the steel mills in the early 1980s led to a mass exodus and a stark decline.

“We had to reinvent ourselves,” said Bill Peduto, Pittsburgh’s mayor.

And they have. Over the last decade or so, the city has been the beneficiary of several overlapping booms. Cheap rent and a voracious appetite for culture have attracted artists. Cheap rent and Carnegie Mellon University have attracted companies like Google, Facebook and Uber, seeking to tap local tech talent. And cheap rent alone has inspired chefs to pursue deeply personal projects that might have a hard time surviving in the Darwinian real estate microclimates of New York and San Francisco.

No one can pinpoint whether it was the artists or techies or chefs who got the revitalization rolling. But there’s no denying that restaurants play a starring role in the story Pittsburgh now tells about itself. The allure of inhabiting a Hot New Food Town — be it Nashville or Richmond, Va., or Portland (Oregon or Maine) — helps persuade young people to visit, to move in and to stay.

Recent census data shows that Allegheny County’s millennial population is on the rise. People ages 25 to 29 now make up 7.6 percent of all residents, up from 7 percent about a decade ago; the 30-to-34 age group now comprises 6.5 percent, up from 6 percent.

Years ago, local boosters proposed a tongue-in-cheek advertising campaign starring a mascot called Border Guard Bob, who would dissuade young people from abandoning the city’s Rust Belt remains. “That has changed dramatically,” said Craig Davis, the chief executive of Visit Pittsburgh. He said the median age in Pittsburgh is 32.8, well below the national figure, 37.7.

That’s good news for tourism; 2,800 hotel rooms have been added in Pittsburgh since 2011. “We’re really using the food scene as a driver of that,” Mr. Davis said. “There’s a reason to come to the city.”

It is also good news for business and culture leaders who seek out young employees and customers. When job candidates arrive, the new wave of restaurants is brandished as a selling point.

“The food scene in Pittsburgh is actually responsible for our landing some best-in-the-world types of people,” said Andrew Moore, the dean of the School of Computer Science at Carnegie Mellon and a founder of Google’s first office in the city.

Google’s presence has since expanded considerably — and almost in sync with the restaurant surge. Pittsburgh’s mayor said the food boom had played a pivotal role in restoring neighborhoods, evidence of an “entrepreneurial attitude throughout the city.”

“Ten years ago, you had some visionaries, some young people who had a dream of owning their own restaurants,” Mr. Peduto said. “They took a risk — they really did believe the place had this amazing potential.”

One of those pioneers was Domenic Branduzzi, who opened a spot called Piccolo Forno in the Lawrenceville area 11 years ago as a way to showcase the specialties that his family had brought to western Pennsylvania from Tuscany.

“I’m an O.G.’’ — an original gangsta — “in the neighborhood,” Mr. Branduzzi said on a recent afternoon as customers filled the cocktail bar at Grapperia, a second Lawrenceville spot of his, which was celebrating its first anniversary. “If I ever want to be transported to my grandmother’s kitchen when I was a kid, I taste one bite of the lasagna.”

In the early days of Piccolo Forno, Mr. Branduzzi was warned that Pittsburghers weren’t likely to take a chance on old-school items like rabbit or wild boar. “People thought it was crazy and that it would never sell,” he said. “And now I can’t take rabbit off the menu.”

Being shielded from crushing rent increases allows Pittsburgh chefs to take risks and cook the way they want to cook without constantly fretting about going under.

“Pittsburgh is the land of opportunity for chefs,” said Justin Severino, another Lawrenceville pioneer whose Cure, which he opened on a dingy stretch of Butler Street in 2010, has won national accolades. He’s got a second baby in Lawrenceville now, too — a brand-new Basque-style pintxos restaurant called Morcilla.

A veteran of the acclaimed Manresa, in Northern California, Mr. Severino, now 38, fled the Bay Area when he realized that he couldn’t even afford a beer and a sandwich with friends, let alone a vacation or a house. In Pittsburgh he saw the capacity for ownership, and change. “While the rest of the country was floundering, Pittsburgh stood on the gas and reinvented itself as a city,” he said.

This is not to say that creating Cure was easy. Lawrenceville still has its fair share of graffiti and abandoned storefronts, but “you should’ve seen that neighborhood five years ago,” Mr. Severino said. “I got to know the prostitutes who worked the corner. I got to know the drug dealers who hated my guts.” He was always calling the police; thieves broke into Cure repeatedly.

Through it all, he stuck to his philosophy: “I’m just going to do what I want to do without regard for what people say they want.”

Early adopters like Mr. Severino, Mr. Branduzzi, Sonja Finn of Dinette, Kate Romane of e2, and Richard DeShantz of Meat & Potatoes proved that chef-driven cuisine could flourish alongside steel-town fixtures like Tessaro’s and Primanti Brothers. The next generation is grabbing that message and running with it.

At Whitfield, the new restaurant inside the Ace Hotel, Brent Young, a native son who had helped build the Meat Hook butcher shop in Brooklyn, lobbied passionately for a job conceiving the whole-animal-fixated menu, and brought in the locally grown chef Bethany Zozula and the pastry chef Casey Shively to run the kitchen. Whitfield opened in December; reaction was quick and unexpected. “On New Year’s Eve, we had a line around the building,” Ms. Zozula said.

In the Strip District, the marketplace zone that Mayor Peduto referred to as “the heart of western Pennsylvania’s food culture,” Ben Mantica and Tyler Benson, two 20-something entrepreneurs who met in the Navy, are bringing the model of a tech incubator to the food world. Their Smallman Galley consists of four kiosks in which different chefs showcase their cooking for 18 months. The chefs pay no rent; the hope is that they’ll build a following and create their own restaurants.

Mr. Mantica and Mr. Benson see Smallman as a way to cater to the tastes of the young employees of Apple, Uber and Google who are starting to occupy new apartments in the area. “We’ve seen this huge demographic shift in Pittsburgh, and now it’s a matter of, ‘What do those people want?’” Mr. Benson said.

To the northeast of Smallman Galley, in Lawrenceville, the chef Csilla Thackray and the restaurateur Joey Hilty, both in their 20s, are trying to carve out their own slice of the marketplace with the Vandal, a casual restaurant that’s open for breakfast, lunch and dinner.

Mr. Hilty grew up near Pittsburgh, and said he had plans to leave for New York or Oregon after college, but “I had too much debt. So I slowly figured out what my contribution would be to the city.” He is glad he stayed. Lawrenceville, he said, is “very youthful and it’s full of unbridled enthusiasm for this stuff.”

But there is ambivalence as well. Young restaurateurs know how gentrification works; they’ve witnessed it in Brooklyn and San Francisco. Rents rise. People get squeezed out. “We all see where it’s going to be in five years,” Mr. Hilty said. “The barrier to entry’s going to be so high.”

Ms. Thackray added, “It’s really cool — and then the bubble bursts.”

Like winning the lottery, being crowned a Hot New Food Town can complicate things. Despite his trailblazing, Mr. Severino has noticed how Lawrenceville’s newer inhabitants view him as something of a square. “Most of those hipsters hate me,” he said with a laugh. “They’ll go out of their way to tell me what a yuppie I am.”

Some of the more thoughtful leaders of Pittsburgh’s cultural youthquake find themselves vexed — worrying that the city they wanted to live in could turn, over time, into its glossy and expensive opposite, a place that evicts older residents and prices out younger ones.

“Look, I like good coffee, I like good bread, I like good food,” said Adam Shuck, 29, who writes an e-newsletter called “Eat That, Read This” and is developing The Glassblock, a web magazine about the city. “I’m torn. I love this stuff, and I’m not going to say I don’t. I welcome and applaud this changing Pittsburgh.”

On the other hand, “there’s also a part of Pittsburgh that has been left out of this excitement,” Mr. Shuck said in an email. “Poverty, food deserts and lack of opportunity and access in historically marginalized communities are big problems in Pittsburgh, and all of the praise and celebration can ring a bit hollow when you consider these realities. Nitro coffee and slow bread are not at the top of your list when you can’t even get to a grocery store.”

The present is exciting in Pittsburgh. The future? That depends.

“We just have to stay vigilant in how Pittsburgh’s redevelopment takes place,” Mr. Shuck said, “fostering the conversation and pressuring government and private capital to work together to do it right.”